Wild for the Pawpaw

Wild for the Pawpaw

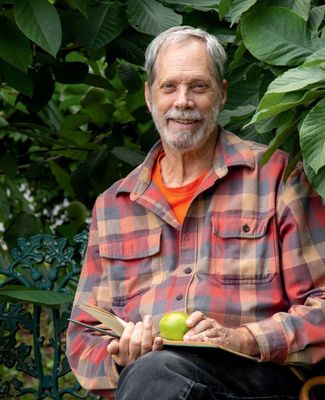

This native tropical-tasting fruit can be foraged, but you might prefer the varieties cultivated by MSU’s Johnny Pawpawseed.

July 15, 2021Admirers have given agricultural economist Neal Peterson, ’80, many nicknames—Johnny Pawpawseed, Papa Pawpaw and even the Mahatma of Pawpaws—thanks to his nearly 40-year effort to popularize America’s largest edible native fruit.

The pawpaw, also known as the bandango or custard apple, may be America’s best tasting and least known delicacy. This kidney-shaped treat, which can be the size of a very large berry or a small baked potato, tastes like a cross between a mango and a banana. It grows on trees in 26 states east of the Mississippi from Michigan to New Orleans. (In fact, Michigan boasts the Paw Paw River and the village of Paw Paw.) Its yellow-orange custardy flesh sports seeds the size of lima beans. George Washington loved pawpaws, chilled. Jefferson planted them. Native Americans ate them for centuries.

They grew in the woods behind Peterson’s childhood home in West Virginia. As a boy, he threw them at his friends but never thought to taste one until he was a graduate student studying plant genetics. “The light bulb turned on,” he recalls.

“It was an epiphany, a revelation. I couldn’t believe that there was a wild fruit that tasted this good.”

At Michigan State, Lee Taylor, a professor of horticulture, mentored Peterson, lending him a yearbook of the California Rare Fruit Growers association. “It was a compendium of all the pawpaw articles they could find. That spurred my interest,” says Peterson. “I got bit by the bug for pawpaws very, very seriously.”

While working for the U.S. Department of Agriculture, Peterson made it his life’s goal to find the best varieties of pawpaws, grow them from seed and spread the pawpaw gospel.

But he faced a big problem. No one had ever commercially bred pawpaws.

A few tasty varieties had been identified, thanks to a 1916 contest sponsored by the American Genetic Association. Armed with information on amateur growers from the yearbook, Peterson set out on weekends and vacations to find long-lost orchards in Virginia, Illinois and Pennsylvania. He rifled through dusty deed books in courthouses and visited small town churches. He phoned county extension agents. He knocked on farmers’ doors. He won landowners’ permission to wander their woods for the remains of abandoned orchards.

By 1982, he had planted 800 seedlings at a University of Maryland research center. In 1996 he had 1,500 trees from which he picked the 18 tastiest varieties. A few years later he patented and trademarked seven of them—Shenandoah, Susquehanna, Rappahannock, Allegheny, Potomac, Wabash and Tallahatchie—which he markets via his company Peterson Pawpaws, whose orchard is in Harpers Ferry, West Virginia.

Mario Mandujano remembers tasting one of Peterson’s pawpaws when he was an MSU student studying horticulture in 1994.

Now a research assistant in the Department of Plant, Soil and Microbial Sciences, Mandujano manages MSU’s plot of pawpaw trees, which include a few of Peterson’s varieties, at the Jackson Roger's Reserve. The department is working to improve the quality and adaptability of the trees for Michigan. Because the growing season is so short in Michigan growers want early fruiting cultivars.

“More recently we began to explore the commercial potential of the fruit,” Mandujano says. “Once growers and Michigan businesses began discussing opportunities to develop products, the MSU team took another look at the market value of the fruit.”

From a business standpoint, they are a tough sell: Fragile, they bruise easily and don’t travel well, and they’re ripe only a few weeks in late summer.

MSU’s team determined the market value was in the pulp, which could be extracted and crushed into puree. Creating puree by hand is easy enough. It’s another matter to produce it at scale and create a business.

To get some answers, Mandujano and Daniel Guyer, a professor in Biosystem and Agriculture Engineering with expertise in post-harvest handling and value-added process development, headed to Italy. There they meet with a fruit processing company, who designed a machine to extract pulp from the delicate fruit. A year later, the machine was in Michigan and the MSU team began extracting and testing pawpaw puree. The team is currently working with Treeborn in Jackson, Michigan, to further improve upon the puree process and to package the puree. The plan is to eventually sell it to ice cream and beer makers.

“We are still working on introducing distinct cultivars that can produce quality fruit and thrive in Michigan,” says Mandujano.

The pawpaw provides a healthy dose of vitamin C and is rich in in riboflavin, thiamine, B-6, niacin, and folate. Vitamin C helps to boost the body's immune system, builds collagen and improves the absorption of iron from plant-based foods.

Today lucky shoppers at farmers markets may stumble across growers selling pawpaws. Peterson agrees with Mandujano they’re best eaten fresh and make luscious ice cream. Small quantities of the pawpaw puree can be purchased online. If you’re interested, you’ll have to act quickly. It’s very popular and sells out fast.

Photos courtesy: Helen Norman

Author: Stephanie Motschenbacher, '85, '92Contributing Writer(s): George Spencer