A Body of Good

A Body of Good

September 30, 2021Milk. It is a staple in many households. The thing about staples is, they are easy to overlook. The everyday is often taken for granted. At Michigan State, much work is rooted in the opposite. Researchers take nothing for granted as they seek new solutions for populations around the globe and right here at home. No surprise. In East Lansing, there is a long history of contributions to the food world, and the world in general. Not least of which is the story of the late Verghese Kurien.

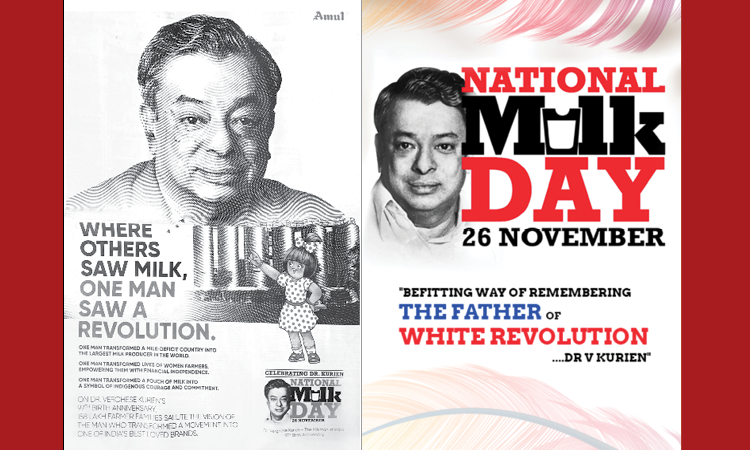

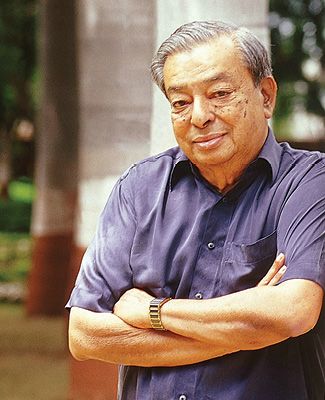

For anyone unfamiliar with the “Milkman of India,” here is a primer: After receiving an engineering degree in India, Kurien made his way to MSU where he earned a master’s degree in mechanical engineering in 1948. When he returned to India the following year, Kurien began working as a dairy engineer at the small Government Research Creamery in Anand—just as the country was in the throes of battle against a milk monopoly.

For years, the Polson brand had been overpowering dairy producers. The giant would buy milk from farmers for next to nothing and sell it for massive profits, while paying little mind to food safety. The country was milk deficient. It was at this time, from the creamery in Anand—now home to the internationally renowned Amul dairy cooperative—that Kurien fought for better treatment and protection for dairy producers of India.

As rural farmers organized local cooperatives, Kurien orchestrated an effort to take ownership of their product, bringing everything in-house. He used his engineering background to build processing plants, and his entrepreneurial mindset to set up marketing campaigns and shipping schematics. That way, local producers would be able to distribute their milk to local consumers. And that meant fresher, safer dairy products for all. In just a few years, the co-op program in Anand blossomed into a movement of millions of farmers, no longer answering to private interests, but rightfully in control of their milk.

The project was such a success in the region, it was named the national model for dairy distribution. This was labeled Operation Flood, in which Kurien helped deliver milk to the masses via farmer-led co-ops across the country.

Today, India is the world’s number one milk producer. And Kurien’s model has been mirrored by China as well as countries in Southeast Asia and Africa.

“He was a real visionary who built a complete infrastructure. Cold storage, transportation, rural management, even schools,” says Amol Pavangadkar (M.A. ’05, Communication Arts and Sciences), professor of practice and a senior specialist in the School of Journalism who is producing and directing a documentary about Kurien.

For the film, Pavangadkar is working on two separate productions simultaneously: an Indian version, which will receive wide release in multiple languages, and an American version that interweaves Kurien’s journey with that of today’s international students. He hopes to have the films ready for release on Kurien’s 100th birth anniversary later this year.

What fascinates him about Kurien? “Of course I knew who he was, but I didn’t know he went to MSU until 2010. And I have been here since ’02. The story is known worldwide but hasn’t been told from an MSU perspective.”

Kurien, who died in 2012, won the World Food Prize in 1989, and was awarded all three Parma awards, representing India’s highest civilian honor. He received the MSU Distinguished Alumni Award in ’91, and an honorary doctorate in ’65. To this day, Kurien’s MSU degrees hang prominently in his family home.

“Above the awards and everything else, it’s about pride in what’s been achieved,” Pavangadkar adds. “He defines the mission and mindset of the premier land-grant university.”

It’s true, Kurien’s influential model has changed the course of food distribution, safety and management systems around the globe. But there’s so much more to it than milk. Creating change, bettering lives and working together to make the right things happen. It’s the kind of Spartans Will that lives on in East Lansing, where today’s minds are combining research with outreach. Globally engaged for the greater good. The Milkman would approve.

GLOBAL VIEW

“I am obsessed with food.” So obsessed that Felicia Wu made it her life’s work. As an advocate and scientist in food safety, Wu’s areas of interest bring together global public health, agriculture and trade. Recently appointed to the United Nations Food & Agriculture Organization Livestock Food Security and Nutrition Scientific Advisory Committee, Wu is working alongside 20 researchers to examine the transformation of global supply chains. This research will assess safety concerns and work with nations worldwide to improve food safety and human nutrition.

“It’s about protecting the population at large from contaminants which are fairly easily preventable,” Wu says of her work. “It’s a matter of applying simple food safety principles.”

But the hurdles are varied, and many simply do not have ways to protect themselves. One major barrier? Electricity. Some places are too far removed from a grid, while others experience sporadic blackouts and unreliable connections.

Lack of electricity makes cold storage a challenge. In the U.S., a complete cold supply chain is the norm. Food that starts cold, stays cold. And while it is a privilege to keep food at safe temperatures in our homes, those precautions can be traced back down the line from supermarkets, to shipping containers, to storage facilities. Other countries are not so fortunate.

Wu’s work at MSU and with national and international committees aims to shed light on food safety solutions. One of those solutions is the development of a dry chain. “After harvest, we can dry food, and it will last for quite a long time,” says Wu. And reducing moisture in the food supply is just as essential here as anywhere in the world.

This is where Brad Marks (’89, Agriculture and Natural Resources & Honors College) comes in. Professor and chairperson of the department of biosystems and agricultural engineering, Marks’ primary focus is improving microbial safety in ready-to-eat foods.

Marks is leading a low-moisture food systems research group as part of a $9.8 million grant from the U.S. Department of Agriculture – National Institute of Food and Agriculture. The project is developing the data and science to help establish safe, consistent operations in the dry foods space. Why is this important? The answer is probably in your pantry. Since the early 2000s, a growing number of E. coli and salmonella outbreaks in the U.S. have been linked to flour. Baking with it is fine, but sneaking a taste of that cookie dough before it hits the oven? It’s not just the eggs that get you.

It’s not just the flour either. Outbreaks on American soil have been linked to pistachios, almonds, walnuts and peanut butter, to name a few.

“Historically, people never thought of dry foods as risky, but we’ve started discovering bad bacteria in these places,” says Marks, “and the pathogens are more resistant and tougher to kill.” Since dry foods lack the moisture that lets bacteria easily thrive, these germs grow ever more resilient in the stark settings. “That which doesn’t kill you makes you stronger is true for bacteria, too.”

While a low-moisture chain could mitigate the likelihood of outbreaks in the U.S., Marks knows it’s more than a numbers game. “We’re not just talking about biology and engineering. Consumer protection, cultural research, economic and business factors are all in play.” It’s a big task, and it’s going to take time.

But that is no reason to shy away from your favorite snacks. “Food incidents are rare in this country,” says Wu, “and we should enjoy that privilege.”

KEEPING IT CLOSE TO HOME

As people seek healthier relationships with the food they eat, they find themselves searching out goods produced close to home. There is no doubt that locally sourced food is fresher, tastier and more nutritious than its mass-produced counterparts. But it is also rich in another way: local food supports local farms.

Lynn Olthof is a graduate student in the College of Agriculture and Natural Resources who grew up on a small dairy farm in West Michigan. Today she is researching ways to help smaller Michigan dairy farms compete in an ever-expanding market.

“The state of dairy has changed in the last few decades,” she explains. “In the year 2000, farms with more than 1,000 cows were producing less than 20 percent of our milk. Now it’s over 50 percent.”

The goal of the project is to help smaller farms expand to remain viable. With a model based around land and herd expansion, facilities upgrades and becoming more efficient overall, Olthof hopes to give farmers the necessary tools to make the right decisions for their operations.

Professor and C.E. Meadows Endowed Chair for Dairy Management Barry Bradford, who is overseeing Olthof’s research, knows what a difference this can make. “If we support small farms, we can bring stability to rural economies, support their people and their communities.”

This type of work is one of the things he loves about MSU. “We can simultaneously address economic, agricultural and social issues, and we’re able to see the real-world impact in our lifetimes.”

The same is true for Olthof, who is optimistic about the future of dairy farming. Now, many people who grew up on farms are reluctant to go back, and it can be difficult for farmers to find good employees. But the industry is quickly moving forward in tech and innovation, opening more and more job prospects.

“People don’t realize the opportunities within the dairy industry,” says Olthof. “Without a dairy background it’s tough to understand.”

That concept is taken seriously at MSU, where strides are being made to introduce agriculture to students who are not from rural areas. The hope is to engage more people in every capacity of the dairy industry, from science and research to human resource and development.

“It’s important for us to be advocates of our own industry.” Olthof’s passion is clear as she speaks of MSU’s new dairy concentration in the Department of Animal Science, which launched fall 2021-22. “The new concentration is a huge step. If we get more people involved, we can support producers, their families and their communities.”

Here in East Lansing, it is true once again: There’s so much more to it than milk.

Author: Tim Cerullo, '08