Growing the Seeds of Knowledge

Growing the Seeds of Knowledge

Endowed Chair Kinitra Brooks studies Afrofuturism—intertwining the past with the future.

July 21, 2020This is a story about how seeds are planted for the future. But like most stories about the future, in order to fully understand it, we need to take a closer look at the past.

In this case, we’re talking seventyish years in the past—in the 1950s.

Two seeds were planted in that decade.

The first happened when Audrey Leslie (nee Munford) graduated from Michigan State University with a B.A. in philosophy and then began work on her master’s in English. She went on to marry John Leslie and become a beloved teacher and administrator for Montgomery County Public Schools in Rockville, Maryland.

The second happened when something called Afrofuturism began to gain traction as “a thing” in its earliest form, and in the ensuing decades it took shape in many ways: in music; in visual art; in performance; and eventually in comics, fiction and fashion.

The two seeds planted in that decade were not related, and nobody could’ve imagined a scenario in which they would eventually take root, become intertwined and grow into the same tree.

![]()

Coming to East Lansing

Fast-forward to the fall of 2019. Kinitra Brooks is standing on the back steps of Linton Hall on the campus of MSU. She’s wearing a green dress and quirky glasses, answering an email on her iPhone. She looks fresh and alive standing among some of MSU’s oldest and most traditional buildings.

We’re supposed to be talking about how she got here. Here, as in on this Earth; but also here, in East Lansing, a scholar of Afrofuturism and the newest member of the English faculty in the College of Arts and Letters.

A few short weeks later, she’ll take the stage to deliver the faculty message at the annual Investiture for Endowed Faculty. She’ll talk about her family, about roots, literal and figurative, and about how they shaped her academic career. She’ll talk about how she’s excited to put down a few roots of her own here at MSU.

Then she’ll walk across the stage, shake hands with President Samuel L. Stanley Jr., M.D., and bow her head to accept a gold medallion.

On the front, it reads “ENDOWED CHAIR, MICHIGAN STATE UNIVERSITY.”

On the back: “Kinitra D. Brooks. Audrey and John Leslie Endowed Chair in Literary Studies.”

Ancestral roots

Brooks comes from rootworkers. Healers. A long line of women who used storytelling and spirituality to pass knowledge from generation to generation. They used that knowledge, and their various botanical concoctions, to cure what ailed their communities.

Her life’s work is based there: on her ancestors, their culture, and where it all fits into the past, the present and the future.

In unearthing and rediscovering these pieces of history, Brooks became part of a community of her own: one that was building a vast field of research centering on Afrofuturism. Brooks’ specific focus is on Black women and the pursuit to upend their stereotypical portrayal as “dangerous” or “demonic” or “voodoo woman” characters in contemporary genre fiction.

These are literary studies as Ye Olde English Professors of Yore have never seen them before, and those studies served her well. To a point.

She worked her way up to the position of endowed professor in the Honors College at the University of Texas at San Antonio. But as her work started to take off, so, too, did the feeling of being hemmed in by old norms. Folks started to have opinions on how she should be, and what she should study as an English professor. And, while they may not have been overt, those opinions impeded her ability to branch out, and they stunted the growth and the diversification of literature as a discipline.

But then she found Michigan State, and the Audrey and John Leslie Chair in Literary Studies, and saw something in both that made her feel like this was a place where she, and her work, could thrive.

The feeling was mutual. In her work, but also in her ebullience, her confidence and her deep investment in growing her field, Michigan State saw a future it wanted to be a part of.

![]()

Freedom and growing ideas

In the classroom, Brooks encourages her students to call upon the same kind of introspection that inspires her. She asks them: Where did you come from? And what parts of your past and your family’s history are you going to bring with you as you create your own place in the world?

Outside the classroom, being the Leslie Chair gives her the freedom to continue asking herself those questions, pursuing the answers and nurturing the seeds of her own big ideas.

“We all have our own different plants and seeds within this world of futurism. Futurism is huge and varied—there are feminist futures and queer futures and Indigenous futures, and MSU has the potential to become a center of excellence in all of those areas, but you can’t do all of that your-self,” she says.

So she’s using her position to help grow other people’s big ideas, too. Brooks and her colleagues from across the university, including the MSU Libraries and the MSU Museum, are laying the groundwork to establish Michigan State as the premier location for the study of race, gender, sexuality and class in the genres of science fiction, fantasy and horror.

So much of Afrofuturism is about world building. What better place to explore that than within the worlds depicted in MSU’s extensive comics collection? And what better place to display related Afrofuturist art and artifacts, and create new visual and digital experiences around them, than within the MSU Museum?

Brooks’ vision for the future is vivid: There will be guest lecturers, visiting artists and research fellows from other institutions, and she hopes to also develop workshops to foster the next generation of writers and students in her field.

The importance of having a critical mass of people and resources devoted to these areas of study goes far beyond simply bringing Afrofuturism to new audiences—or, for the staid, bringing something new to Michigan State and to the larger institution of Ye Olde English Department of Yore.

“Afrofuturism isn’t just about Black people in the future,” Brooks says. “It’s about changing and expanding race, gender, sexuality, class—all these markers of identity. Afrofuturism is a recovery project: bringing together the stories and the traditions and the histories that we lost during the trans-Atlantic slave trade, during Jim Crow, during Jane Crow. Then weaving everything together so we can decide what we want to take with us into the future, and what we’re going to teach our own kids.”

![]()

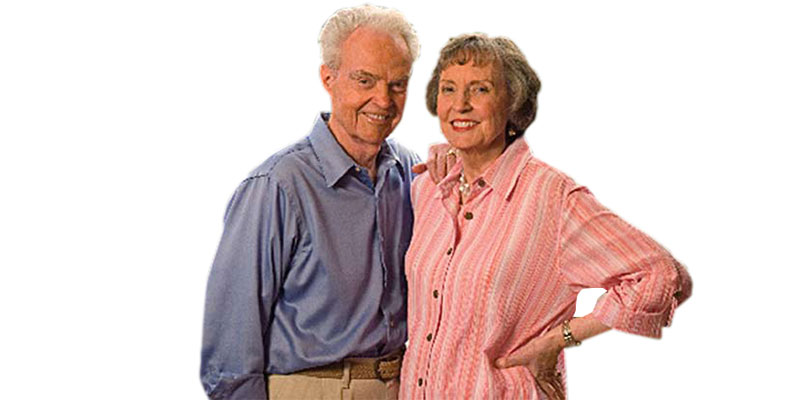

Audrey and John Leslie

We don’t know, exactly, what sort of stories, traditions and histories Audrey Leslie learned about as a student of philosophy and English in the 1950s, but whatever they were, they stuck with her for life, and she was proud to have learned them at MSU.

So in 2005, Audrey Leslie and her husband, John, sat down and wrote out some instructions in their estate plans. When they died, a gift of $2.5 million would be put in an endowment at MSU to establish the Audrey and John Leslie Endowed Chair in Literary Studies.

“The study of literature improved my understanding of the human condition,” Audrey said when she and her  husband made the gift. “And the study of the development of our language improved my appreciation for the power and versatility of English. Everyone can benefit from these studies.”

husband made the gift. “And the study of the development of our language improved my appreciation for the power and versatility of English. Everyone can benefit from these studies.”

Audrey added: “Establishing such an endowment gives us a unique opportunity to help maintain the quality of a program we want to see perpetuated, and gives us a feeling that what we believe is important will continue to be passed on to future generations.”

The seeds were planted. They were watered. Their roots intertwined the day Kinitra Brooks came to Michigan State. And now they’re growing into a pretty fantastic tree.

Author: Devon Barrett, '11