The Great Embrace

The Great Embrace

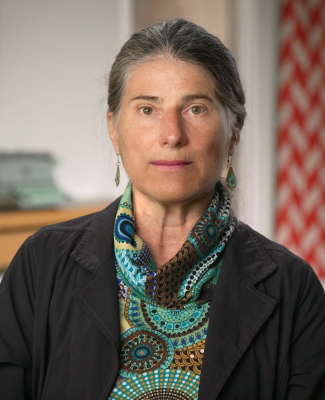

A pioneer in the field of ballast treatment technology, Allegra Cangelosi, M.S. ’87, is helping to keep invasive species out of the Great Lakes.

May 30, 2022Shortly after graduating from MSU with a master’s in resource development, Allegra Cangelosi, ’87, was tasked with addressing an intricate problem threatening the Great Lakes ecosystem—aquatic invasive species. Cangelosi recalls an explosion of the Eurasian ruffe (a member of the perch family) in Duluth-Superior Harbor as the first warning of just how detrimental invasive species could be to the region.

With no natural predators and a faster maturation cycle, the ruffe out-competed native fish species for food and habitat, leaving them reeling. The region was also victim to many additional invasive species, which were being routinely transported to the Great Lakes from overseas in the ballast water of cargo ships. Cangelosi was drawn to the issue of invaders. “It wasn’t just one state’s problem, one city’s problem,” she says. “It was about a region caring for a shared resource.”

Then working for former Ohio Sen. John Glenn as the director of the bipartisan Senate Great Lakes Task Force, Cangelosi had to figure out how to limit the introduction of critters from commercial shipping vessels’ ballast water. For our land-dwelling audience, ballast water is the extra weight added to a ship after it unloads its cargo. That counterweight is what keeps them stable at sea. In commercial vessels, ballast water can reach millions of liters, and when you’re pulling in water from your destination, you’re also sucking up the fauna that lives there. Upon arrival to the Great Lakes, vessels dumped their ballast water—and stowaways—before loading their next shipments. According to the Environmental Protection Agency, that practice introduced 30% of the invasive species to the Great Lakes.

Cangelosi’s team worked to implement legislation that would require ships to exchange ballast before entering the Great Lakes. It wasn’t all smooth-sailing; Cangelosi describes “incredible skepticism within the maritime industry. That if you exchange your ballast water, the ship will start bobbing like a cork, it’ll tip over. It’s not structurally made for that.”

With the threat of closing the St. Lawrence Seaway—the connector between the Atlantic Ocean and the Great Lakes—the commercial shipping industry got creative with a method for exchanging ballast while plying on the high seas. New water came in while old water went out, dumping the freshwater critters into salty seawater where they were less likely to thrive.

Ballast exchange had issues. The method burned more fuel and could only be safely performed when sea conditions were right. This pushed Cangelosi into researching onboard ballast treatment, a prospect that was also met with skepticism. Cangelosi was particularly interested in filtration as it would minimize additional chemical treatment. In 1997, with help from the Great Lakes Protection Fund, Cangelosi’s Great Lakes-based team tested an onboard filtration system on the Canadian Laker MV Algonorth, proving the method was effective. That research was critical in supporting the advent of national and international policies directing ships to treat ballast water.

In 2021, the Great Lakes Protection Fund recognized Cangelosi’s work with the Great Lakes Leadership Award. As a senior researcher at Penn State Behrend, she continues to advocate for the region. “We can’t take [the Great Lakes] for granted,” she says. “We have to actively learn how to take care of them or we’ll lose them. We have to embrace the Great Lakes.”

Author: Alex Gillespie, '17