The Power of Basic Science

The Power of Basic Science

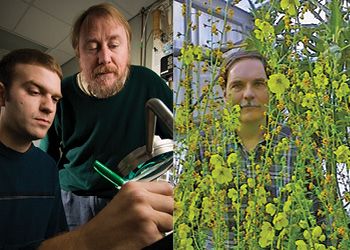

“This experiment has shown us so much about the evolutionary process in microbes and spurred so many new questions,” said Richard Lenski, who launched the experiment in 1988 as a young faculty member at the University of California, Irvine, and brought it with him to Michigan State University in 1992.

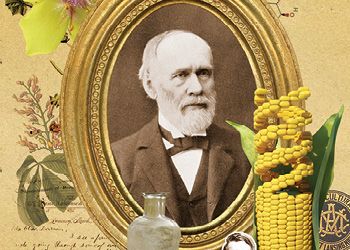

October 21, 1920While Frank Telewski patiently waits for an opportunity to extract one of Wiliam Beal’s Bottles, Richard Lenski, a professor in the Department of Microbiology and Molecular Genetics, goes to work in his lab inside MSU’s Biomedical and Physical Sciences Building.

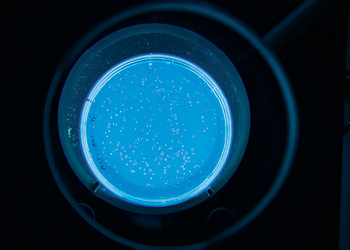

As he or a lab member had done every day for the past 32 years, Lenski took 1 percent of E. coli bacteria from 12 different flasks and placed each sample into fresh media. The 30-minute task represents a grinding effort to gain rich insights into the process of evolution. Over the past three decades, more than 100 graduate students, postdocs and undergraduates at MSU and in labs around the world have engaged with Lenski’s long-term project, studying changes in the bacteria’s growth rates, cell sizes and shapes, physiology and genetic code. Lenski’s lab also does periodic quality controls, freezing samples to provide a record that Lenski’s team can later compare against current samples.

Like Beal, Lenski holds an intense interest in nature’s inherent mysteries, an enthusiasm for nature that compels him to drill deeply into basic science exploration capable of propelling humanity and understanding. His guiding inquiry with the E. coli experiment: How repeatable is evolution?

And like Beal, Lenski isn’t afraid of time.

“The longer we can watch, the more opportunities there are for organisms to do interesting things,” Lenski said. “Evolution as a process is about time.”

But time can’t be rushed, and Lenski, an evolutionary biologist, once nearly ended his experiment. After a decade of seeing a slowing rate of change in his bacteria and convinced the project had run its course, he told his wife and colleagues that he was shutting it down. They all urged him to reconsider.

“Fortunately, I’m easy to convince,” Lenski joked.

In 2003, 15 years after the experiment’s birth, Lenski’s team noticed a change in one of the flasks. Though Lenski initially feared a contaminant, his team soon determined that the bacteria in one flask had begun consuming citrate, a previously untapped source of energy for the bacteria in their culture medium.

Since that breakthrough, Lenski said the experiment has continued to surprise. The bacteria are adapting in complex ways, generating their own ecosystems within the flasks and growing at faster rates. The E. coli, in fact, surge through seven generations each day, and the experiment has now surpassed 73,000 generations.

“It’s revealed new things about the evolutionary process that we hadn’t even imagined at the 10-year mark. I was naive for thinking a decade was a reasonable amount of time for an experiment like this,” said Lenski, whose project has been powered by technological innovations and discoveries, including genome sequencing, that didn’t exist when it began.

The basic science that Lenski’s lab conducts serves as a springboard for much of applied science, driving insights that inform fields from medicine and agriculture to computing and industrial processes. Amid the much-publicized anthrax scares following the Sept. 11 terrorist attacks, for instance, Lenski advised federal agencies on how to identify the origin of anthrax spores.

Summoning Beal’s spirit, Lenski said: “Part of the human experience is understanding nature and the universe in which we live. It’s fascinating to dig into the minutiae and to see how vast and rich the universe is.”

While Beal’s experiment outran him and will eventually stretch 176 years beyond his death, Lenski said he hopes his own experiment continues in perpetuity. “It’s picking up steam and shows no signs of slowing at all,” he said. “There are more exciting surprises ahead.”

Adopting a broader perspective

At the BEACON Center for the Study of Evolution in Action, a 10-year-old National Science Foundation-funded center housed on the MSU campus, biologists, computer scientists, engineers, philosophers and other academics gather to study evolution with the aim of applying that knowledge to real-world problems— with viruses, therapeutics, conservation and automobile safety among the topics the center has addressed.

Though BEACON leverages high-tech computers to scale its analyses, essentially evolving organisms in a digital world, its work is rooted in centuries-old questions about long-term processes in nature. BEACON is, in effect, the contemporary age’s high-powered descendant of Beal’s whirling mind.

“The questions we’re asking are slightly different than what Beal was asking, but they’re still long-term biology questions,” BEACON Director Charles Ofria said. “We’re keeping the spirit of his work intact, though technology is allowing us to push the bounds of research to areas Beal only could’ve imagined.”

BEACON leans heavily on an interdisciplinary approach to fuel its cutting-edge study, mimicking the prying, multifaceted outlook that guided Beal’s life. More than 100 MSU faculty are involved with BEACON at some level, including experts in genetics, game theory, ecology, applied evolution, modeling, robotics and high-performance computing.

“Fundamentally, BEACON is about trying to understand the world around us from varied perspectives, to get people across disciplines talking to broaden understanding,” said Ofria, a professor of computer science and engineering, adding that he came to MSU because interdisciplinary approaches were supported, even expected, not merely encouraged.

Such is MSU’s present, yes, but equally its DNA, exemplified by Beal—a campus founding father who buried bottles for future scientists to study while simultaneously teaching courses in English and promoting new approaches to instruction in an effort to inspire diverse thinking and idea exchange.

“I think Beal pushed MSU down this path of multidisciplinary research and paved the way for something like BEACON to thrive,” Ofria said.

Added Lenski, who works closely with Ofria, philosopher Robert Pennock and graduate students in areas like mathematics, computer science, physics and engineering on a range of projects beyond his signature E. coli experiment: “Beal was thinking broadly and there’s a lot of that at MSU, a lot of pot stirring. It’s a fabulous place to do interdisciplinary research.”

MSU’s willingness to explore some of basic science’s most enduring questions from a variety of perspectives blossomed in the university’s earliest days with Beal as that culture’s ardent champion. It sticks here because it took root here, nurtured by Beal’s successors.

“A lot of scientists have a curious mind and a broad perspective, but Beal was truly different and unique,” Telewski said. “He always seemed to have access to the bigger picture and used that to his advantage to address important scientific questions that could advance the world, connect people and drive new exploration.”

And that’s quite a legacy to leave.

Contributing Writer(s): Daniel P. Smith