What Beal Built

What Beal Built

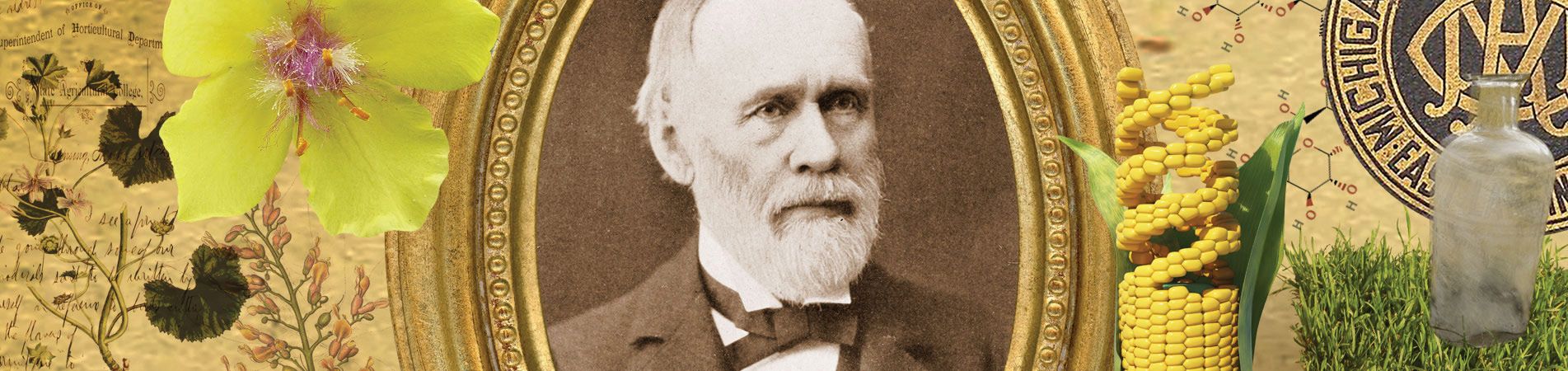

Nearly a century after his death, the ambitious, curious and forward-thinking spirit of pioneering MSU professor William James Beal endures and inspires.

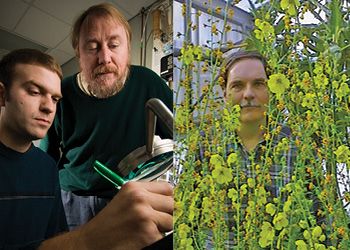

October 21, 2020On a silent spring morning in 2000, Frank Telewski marched across the MSU campus with a colleague at his side and a flashlight in his hand. Arriving at a nondescript patch of land, he planted his knees on the ground and, cautiously and methodically, began pushing a trowel into the East Lansing soil.

As Telewski, a professor of plant biology, extracted scoops of earth, a mounting pile at his side, his heart raced with anticipation and excitement over a moment some 120 years in the making. His colleague—the late Jan Zeevaart, a faculty member in the Department of Plant Biology—looked on with his own sense of wonder and awe, for they were adding their names to the world’s longest-running scientific experiment. Twenty years later, Telewski was hoping to repeat the effort with plant biologists David Lowry, Marjorie Weber and Lars Brudvig, but the coronavirus outbreak disrupted their plans. The only other time that happened was in 1918; ironically, it wasn’t the Spanish Flu pandemic but an early frost that delayed the scientists.

In 1879, William James Beal, one of MSU’s pioneering professors and most enterprising souls, dedicated this unassuming slice of the campus to his capstone experiment, one designed to outlive him and help future scientists address some of nature’s most tantalizing riddles.

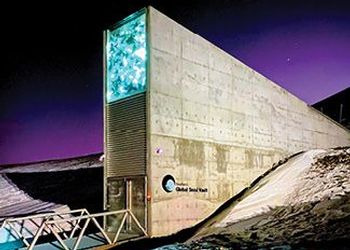

Beal buried twenty 3-inch-by-7-inch narrow-necked bottles, each containing 50 seeds from 23 weed species, in this soil. Every five years, he pulled one of the uncorked bottles from the earth, extracting six during his lifetime, to examine the seeds and test their viability. Upon leaving MSU in 1910, he instructed his successors to do the same, though his project’s heirs later pushed that time frame to 10, then 20 years. The goal: to understand how long seeds remain viable in soil, a pressing question to Beal and late-19th-century farmers and one still relevant in the modern agricultural world.

As Telewski gently pulled a bottle from the soil, he brushed away the dirt and marveled at the scientific and symbolic nature of what he held. As the central caretaker of an experiment that began amid the post-Civil War presidency of Rutherford B. Hayes before being passed down through generations of MSU scientists, Telewski carried the bottle to his campus lab. There, he and Zeevaart spread its contents over a sterile soil mix. Over the next two weeks, the group would follow the seeds’ germination before transplanting the mixture into pots for continued study.

“I feel protective of his legacy,” said Telewski, who first learned of Beal’s experiment as a graduate student at Wake Forest University in the 1980s and has now spent the past 27 years of his career as an MSU faculty member tracking Beal’s sizable footprints. “Beal was a curious mind who wanted to understand the very nature of things—some questions only time can answer—and that’s a legacy I’m trying hard to carry on.” Telewski isn’t alone in embracing Beal’s industrious spirit and honoring his unrelenting pursuit to understand the world through an ambitious array of multifaceted projects and diverse perspectives. Ninety-six years after his death, Beal’s legacy endures in ways as wide-ranging as his interests.

A life devoted to understanding

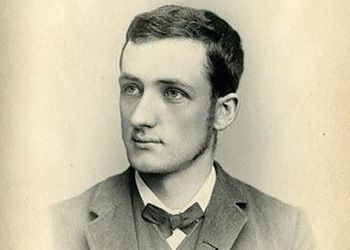

Born in Adrian, Michigan, in 1833 to pioneering Quaker parents from New York state, Beal was raised in a log cabin amid virgin forested lands, a seminal experience that cemented his connections to and fascination with nature. He earned a pair of degrees from the University of Michigan before continuing his education at the University of Chicago and Harvard University, where he studied under legendary American botanist Asa Gray.

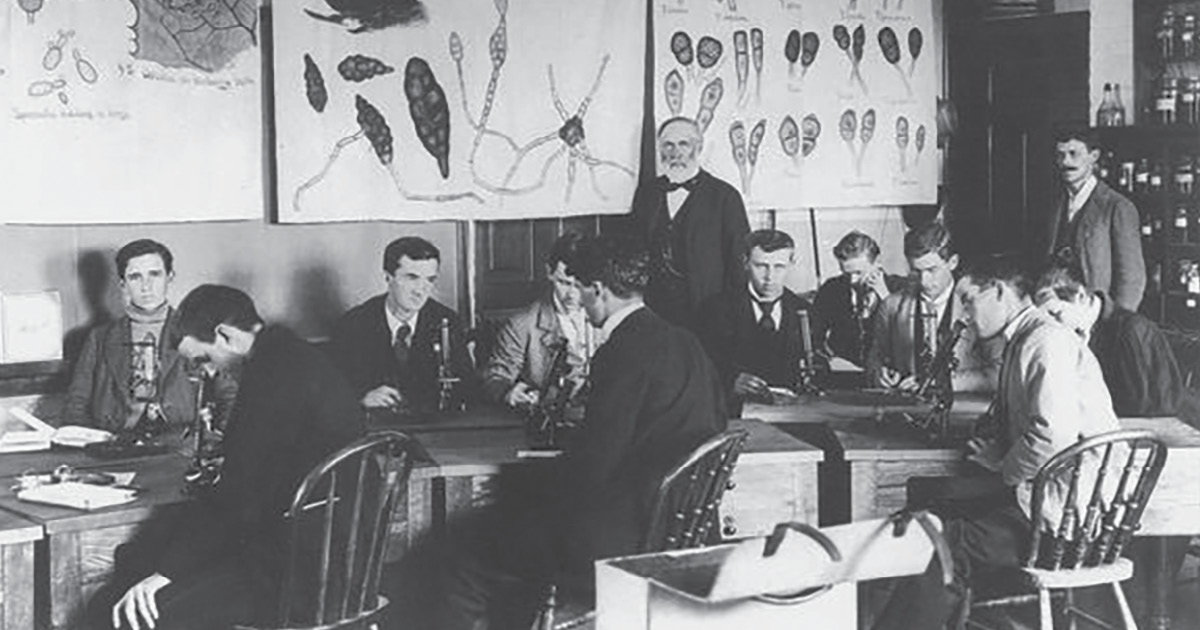

Beal returned to Michigan in 1871 as a lecturer on botany at Michigan Agricultural College (M.A.C.), the higher-ed precursor to MSU. For the next four decades, Beal was a scholarly force at the fledgling institution, pushing bold scientific research to understand the nature of the world, developing pedagogy to enhance student learning and driving interdisciplinary collaboration generations before the term entered the mainstream lexicon.

“Dr. Beal is one of the group of men whose work was responsible for the beginnings of M.A.C.,” his obituary in The M.A.C. Record said.

Beal taught classes in botany, horticulture and forestry, educating and inspiring a long line of environmental enthusiasts and laying the foundation for MSU’s rise as one of the world’s top research institutions. A Renaissance man with a far-reaching mind, he also taught courses in English, history and civil engineering. The maxims he preached demonstrated his pragmatic, thorough approach to science and the world at large, including: “Details and facts before principles and conclusions,” and “An eye trained to see is valuable in any kind of business.”

In 1873, he founded MSU’s W.J. Beal Botanical Garden, now the nation’s oldest continuously operated university botanical garden. He fashioned the 5-acre space as a living lab and hands-on experiment station for his students and research. He also spearheaded the planting of trees across the campus, including the white pine lining Hagadorn Road, and led students in the design of the arboretum between Mary Mayo and Campbell Halls.

“He was like a child eager to open each new package that nature presented, to see what it contained … [and he] infected his students with this enthusiasm to know nature, and to know it firsthand,” The M.A.C. Record wrote of Beal, who shunned alcohol, tobacco, coffee and tea in favor of habitual exercise.

Beal’s touch extends far beyond the MSU campus and the students and colleagues with whom he interacted.

In 1887, when much of Michigan was still only slowly shedding its frontier ways, Beal and MSU mathematician Rolla Carpenter created “Collegeville,” a residential neighborhood that would morph into the modern-day East Lansing.

Called the “Father of Michigan Forestry,” Beal also was an early champion of forest conservation and reforestation after years of lumbering had cleared the northern half of Michigan’s Lower Peninsula of white and red pine. Beal, who would serve as director of the Michigan State Forestry Commission, encouraged farmers to begin planting trees—oak, pine, spruce and maple among them—arguing that trees would be economically useful to farmers on land unfit for other crops.

Beal and Liberty Hyde Bailey, a star pupil who would later shine in his own professional pursuits, also took wagon trips to create agricultural experiment stations in northern Michigan outposts like Grayling, Harrison and Oscoda. On an 80-acre plot in Grayling, for instance, Beal oversaw the planting of 41 species of trees. The Beal Plantation survives in 2020, a historical site largely considered the oldest documented tree plantation in North America.

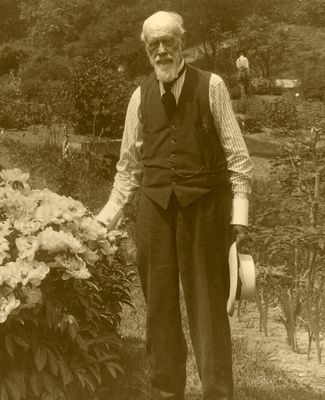

“Beal’s mark on the land is still with us today,” noted Telewski, who tends to some of that land himself as director of the Beal Botanical Garden and Campus Arboretum.

So, too, remains some of Beal’s most complex research, including studies of turfgrass—Beal conducted the nation’s first turfgrass research and his two volumes of “Grasses of North America” remain seminal works in that field—and hybridized corn. After reading Charles Darwin’s work on hybrid vigor, Beal penned a letter to the acclaimed scientist asking about hybrid vigor’s potential applications to corn, a crop that hadn’t yet been manipulated. Darwin replied and encouraged Beal’s experimentation. That optimistic push fueled Beal’s most notable contribution to the greater world: hybridized corn. In conducting the first controlled crossing of corn lines in 1878, Beal set the stage for the diverse varieties and increased yields of corn present today.

Beal’s mind seemed in constant motion, ever investigative and questioning, endlessly craving knowledge. Over the course of his career, he published more than 1,200 papers and seven extensive texts.

“I don’t know when he slept,” Telewski said of Beal, who once said that he “studied and labored industriously because it gave [him] joy.”

The bottle experiment perfectly characterizes his ambition and curiosity, his grand attempt to advance science, contribute to understanding and unlock some of nature’s mysteries—even if that knowledge would come well after his time. There’s always something to be discovered. Beal understood and rejoiced in that twinkling reality.

“It takes a special kind of mind to see beyond his own mortality,” Telewski, 64, said. With five bottles remaining in Beal’s experiment, the last one will be unearthed in 2100.

While Beal left East Lansing in 1910 and died in 1924 at the age of 92, he instilled a probing, interdisciplinary ethos that endures at MSU. He set a pace and a commitment to studying the nature of things for the betterment of humanity that others embrace today with purpose and passion. He was a Spartan before we were Spartans, and his influence at MSU can be seen in concrete, ongoing ways.

Contributing Writer(s): Daniel P. Smith